People don’t always respond.

You write an email, you send a text, or if you’re adorably old-fashioned, maybe you mail a card, but the recipient sometimes just doesn’t get back to you. It’s nothing to stress about. It’s usually more about the recipient than it is about you: life got busy, an unexpected move, a new project at work.

But I am not one of these missing people. To exchange written pleasantries with me usually means to commit to years of correspondence. You’ll never have to worry about hearing back from me, because I will always respond. And if I don’t, you can be sure it’s not because I got busy. It’s not just about you, but it’s not only about me, either. It’s about us.

I was just your average philo-Semitic publishing assistant doing some freelance writing on the side when I first reached out to Faiga Sarah. I was working on a piece, you see, and I wanted to mention something I had read about the Breslov Hasidim: that they took sixty minutes each day during which they did absolutely nothing, hoping to allow “the repressed soul to come to the fore and be free.” They called this time “the dead hour.” It sounded sort of like meditating, except that instead of centering your mind when it wandered, you just let it roam.

The prospect of sanctioned daydreaming was irresistible to me; I had such fond memories of woolgathering as a child, but now, as a twenty-something, a perhaps-unavoidable imaginary audience syndrome had made me too timid to acknowledge my deepest desires even to myself, in my own silent inner sanctum.

The Dead Hour seemed the perfect balm for my restless brain—and you could do it lying down, to boot. Problem was, it didn’t exist. Or rather, I could only find it in a single text, and the writer of said text was not known for his academic rigor. So I went digging, and found myself emailing Faiga Sarah, a Breslov blogger.

Faiga Sarah had published numerous essays on her site about growing up in an irreligious household and ultimately finding her way to frumkeit and Breslov Hasidus, known for its focus on joy and individual prayer. She often wrote about how Breslov philosophy helped inform the work she and her husband, a trained therapist, did with drug addicts.

Had she ever heard of the Dead Hour? Where could I find a more detailed description of it? Could it be possible that the idea was an accidental melding of the concepts of hisbodedut, the solo, free form prayer prescribed by Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, and the “Dead Hasidim,” as many call his followers, who declined to appoint a rabbinic leader after Reb Nachman passed away?

“Well,” her response began, “THIS is certainly the most interesting email I’ve received today!”

And thus what began as a random inquiry developed into two years of something resembling a friendship (let-down alert: the Dead Hour isn’t really a thing). Over the course of our correspondence, we sent a flurry of emails back and forth, me often talking about my slow but steady walk toward my conversion to Judaism, she about the satisfaction and serenity that infused her life since she became a Breslover ten years prior.

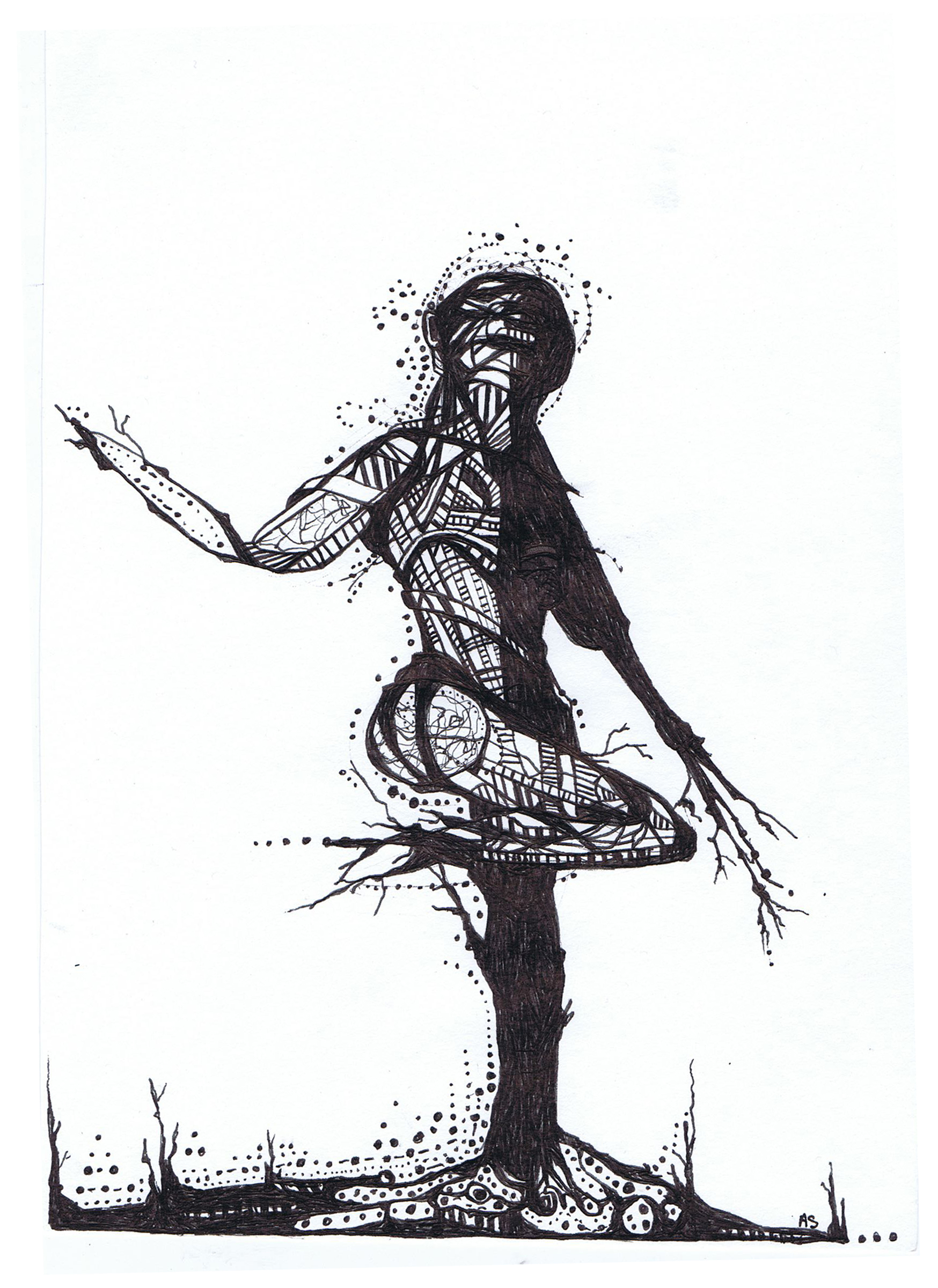

Artwork by Amanda ShafranDetails about Francesca—her given name, and the person she was before she “returned” to Judaism—were scant, but every so often she’d mention that she’d once partied with Bono, or lived in a white adobe hut outside Taos, or had a dog that she allowed to eat ice cream in bed. For reasons I couldn’t quite determine, I pounced on these bits of info the same way one might relish hearing of a new lover’s past. In fact, it wouldn’t at all be an exaggeration to say that I had a crush on Faiga Sarah, she who wrote in a lively voice of a mysterious, dramatic past and a pious, content present. That was what I wanted: to leapfrog over the spiritual confusion that had defined nearly all my life and arrive at a happy resting place with G-d.

So many times in the past, I had automatically associated Hasidim, with their robust traditions and close families, with that kind of stability. My intellect told me it wasn’t as simple as all that, but my heart stubbornly refused to abandon this belief. The way Faiga Sarah told it, it was my head, not my heart, that was the problem. Hasidism did offer its followers happier lives, smoother marriages, and of course, a deeper connection with the Divine. Breslov Hasidism, she added, also taught you how to love yourself.

“In Breslov Hasidus, we learn that a lack of belief in self is a kind of atheism,” she wrote once. “It is a beautiful insight that can make your entire worldview shift. It made me giddy with delight when I first learned this.”

I smiled hopefully at those words on the screen. Me, weary after years of therapy, hater of anything that smelled of self-help. Somehow, when she wrote these things, they didn’t sound saccharine or stupid; they sounded beautiful. It was an irresistible pitch.

Maybe ten months into our friendship, she sent me an audio clip of a shiur she did with a group of women in Boro Park, where she lived, and it seemed to confirm Reb Nachman’s promise—there was real mirth in her voice. I was in Albuquerque on a writing assignment when I listened to these classes; it was December, dry and cold in the Southwest, and I was staying at a retro-style motel on a lonely stretch of highway near the eerily deserted historic downtown. It was the kind of thing that sounds romantic on the page—jet-setting journalist exploring a strange and gritty new place—but was so sad and lonely in real life. Both nights, I fell asleep to Faiga Sarah’s clear, soothing voice telling me Hashem was with me, that He loved me, that He thought I was precious.

I met Faiga Sarah exactly once, on a bright spring Sunday when my then-boyfriend had gone into the office. I dressed in my most fashionably modest outfit and then took the subway down to Boro Park to have tea at her house. The building where she lived was a wide brick structure named the Sagaponak, which I immediately assumed to be a failed reference to the chic Hamptons village. Faiga Sarah practically skipped out of her second floor apartment in padded slippers and yelled down the stairs to me. I caught a quick glance at her moon-face as she leaned over the banister and instructed me to come to the second floor. In that brief glance, I formed a vision of her hair as an auburn shade, but of course it was hidden beneath a black Lycra snood. She was younger than I had expected, and her ample torso pressed against her stretchy long-sleeved shirt. I had pictured her as grandmotherly in appearance, maybe even frail, but here she was full-figured, and probably younger than my mother.

That afternoon, we sat in her living room and chatted like schoolgirls about the topics that dominated our letters: Torah, secular society’s shortcomings, the ways Rebbe Nachman’s wisdom underpinned modern psychology.

And then she said something that stuck with me like an earworm. Mothers came up somehow, and, waving her hand as if to imply it weighed on her with all the weight of air, she said, “Well, I haven’t talked to my mother in years now, but anyway…”

It was just a quick linguistic path to a new subject, but the admission stayed with me. Suddenly, a fuller picture of Faiga Sarah began to come into focus. This was a woman who left a whole life behind to become the vessel of jubilant piety that sat before me. Friends, lovers, even parents had all receded into the distance. The messy sophisticated society, with its equivocations and rationalizations—she practically spat when she uttered those obscenities—left for scorched.

I realized in that moment that I could never be my whole self in the context of my friendship with Faiga Sarah. I wanted her goodness and light, but I knew I’d never be able to give up some comforts offered by the big, bad world: its literature, its silly chatter, an occasional session of channel surfing. Maybe I wasn’t as strong as she was. Maybe I didn’t have the emunah that she did. Or maybe it was she who was willfully myopic, rendered daft by her desire for the simple life. Whatever the case, as she walked me down sunny 14th Avenue to the subway, I knew the first time we strolled next to one another would probably be the last. When we reached the station, I almost yelped. “Let me stay,” I could have said. “I’ll sleep on your couch. We can say shacharit together every morning. You can teach me to be good.” But instead I hugged her tight, climbed the stairs, and boarded the next train back to my world, with all its ugly, intense, fascinating complications.

Every so often, I’ll get a note from Faiga Sarah. She tries hard to be all warm and accepting, but I sense a little disappointment in the subtext. “I haven’t heard from you,” she’ll write. “I assume you are married now?”

I want to tell her that I did convert, with a rabbi of whom she probably wouldn’t approve. I want to tell her that I miss her. I read her name with a little pang of guilt when I do my daily skimming of my inbox to see what I can quickly respond to. A few times I even challenge myself to delete it––people don’t always respond, I tell myself. People fall out of touch. It’s nothing to stress about.

But then I reconsider, and leave the email there. I want to see her name, so I remember her, so I am reminded that reliability counts for something. Maybe even next Yom Kippur, I’ll apologize to her.

--------

Kelsey is the author of the book "How to Disappear Completely: On Modern Anorexia" and has written for New York Magazine , The New Yorker, Harper's, and Vice, among other publications. She lives in London and is working on a book about religious conversion.

comments powered by Disqus